The Increasing Frequency of Terms Denoting Political Extremism in U.S. and U.K. News Media

Introduction

I summarize here a published study co-authored with Eric Kaufmann where we examine longitudinally the prevalence of terms denoting far-right and far-left political extremism in more than 30 million written news and opinion articles from 54 news media outlets popular in the United States and the United Kingdom.

Results

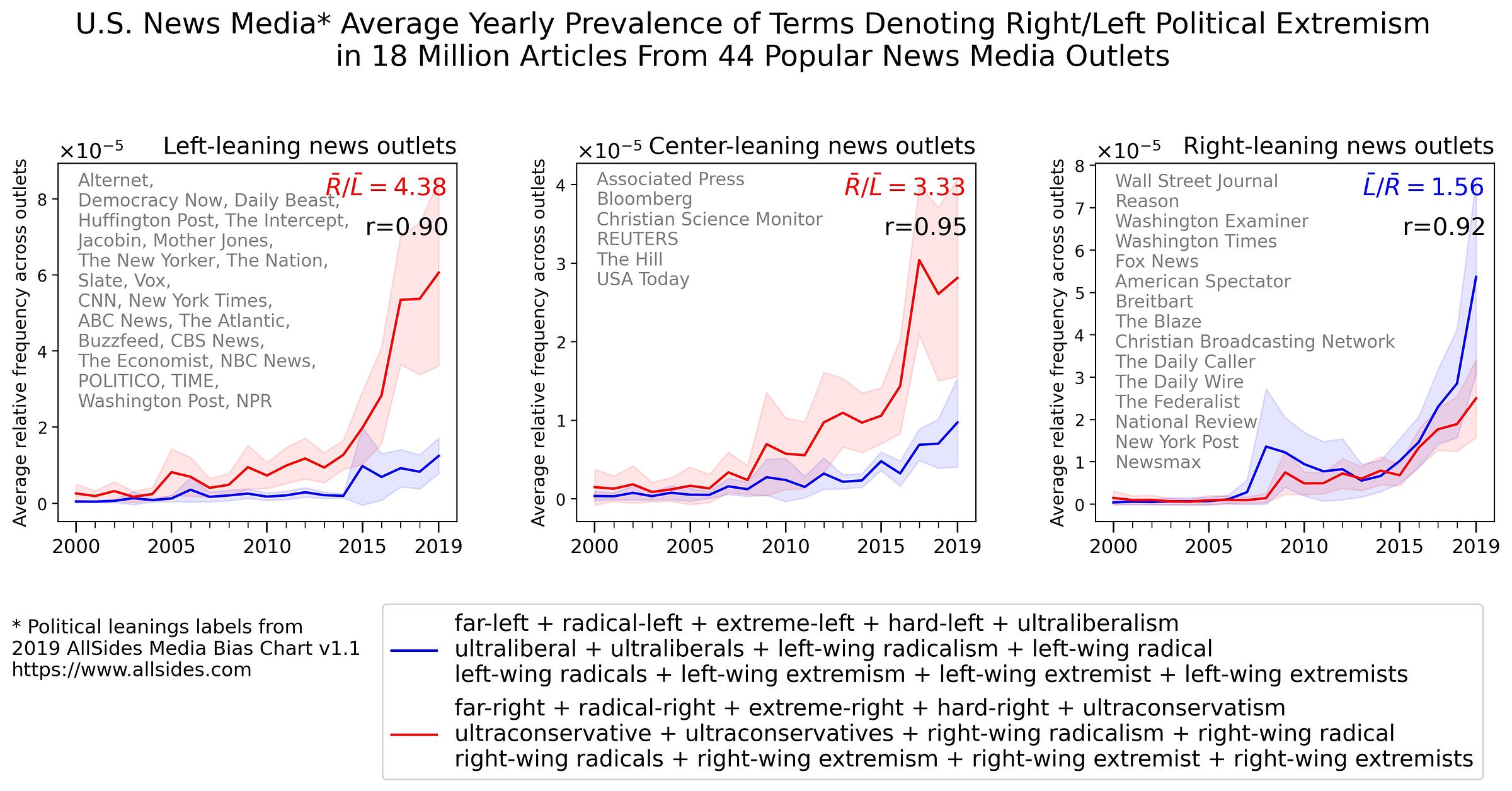

We find that the usage of both far-right and far-left denoting terms appears to be rising across U.S. news outlets regardless of their ideological leanings. On average, left- and center-leaning news outlets tend to mention right-wing extremism substantially more than left-wing extremism. Right-leaning news outlets show an opposite but milder pattern. Right-leaning news outlets are about two times more likely to mention right-wing political extremism than left-leaning news outlets are to mention left-wing political extremism

We replicated the analysis above for 10 popular news media outlets based in the United Kingdom. The results show rising overall usage of terms denoting political extremism and a higher prevalence of far-right-denoting terms than far-left-denoting terms, even in right-leaning news media. Right-leaning news outlets in the U.K. are, on average, five times more likely to use far-right denoting terms than left-leaning news outlets are to use far-left denoting terms.

Examining news outlets individually shows that the growing usage of terms denoting political extremism is visible within most individual U.S. outlets.

Replicating the analysis above for all the individual news outlets in the U.K. also shows growing usage of terms denoting political extremism across most outlets, but the trend is more marked for far-right denoting terms.

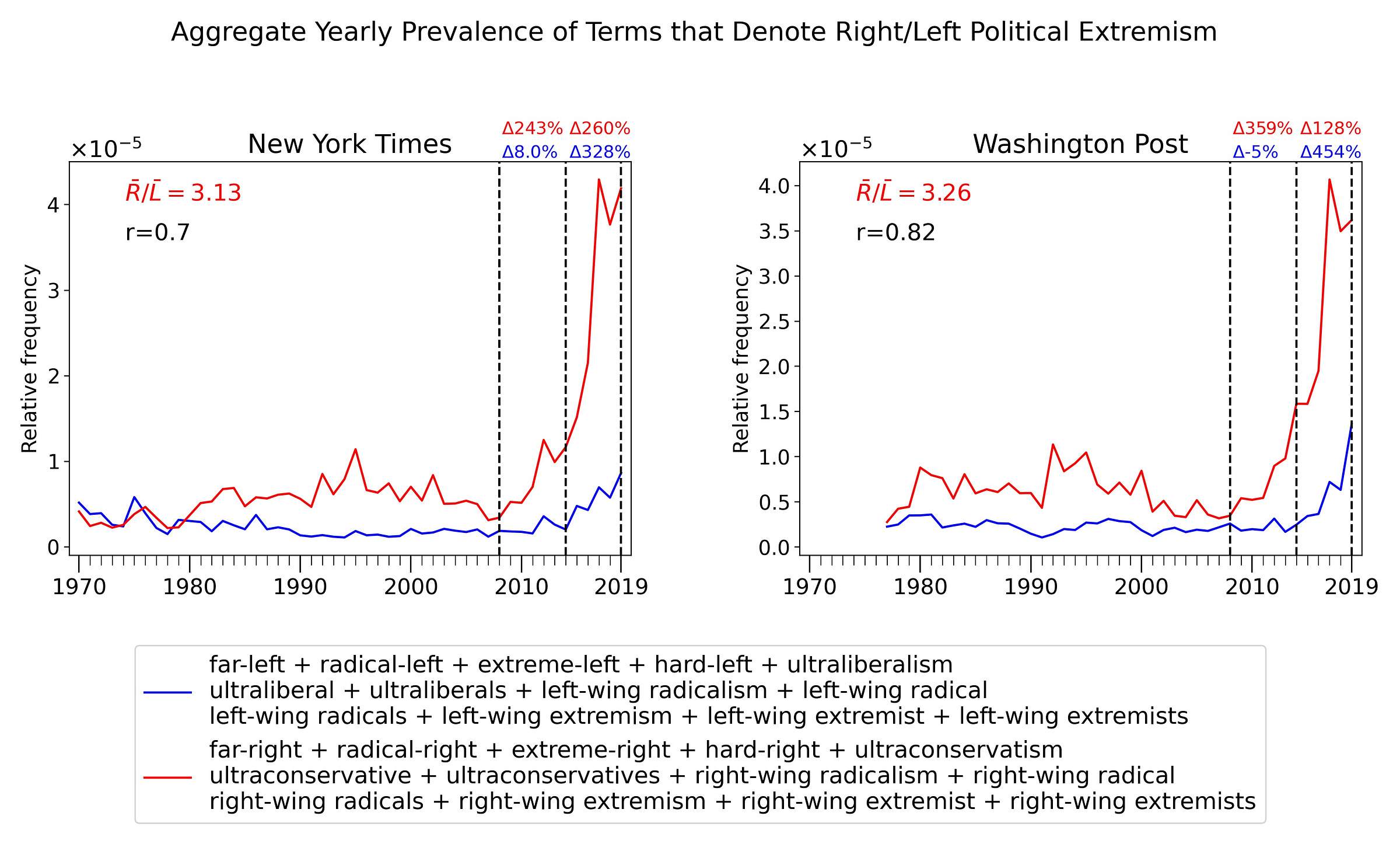

We next examine the prevalence of terms signaling political extremism for a longer time frame (1970-2019). In the 1970s, The New York Times used terms denoting far-right and far-left political extremism at a comparable rate. Since the 1980s, however, both in The New York Times and in The Washington Post, the prevalence of right-wing-extremism-denoting terms has been, on average, more than three times higher than the prevalence of terms denoting left-wing extremism.

Usage of terms denoting right-wing political extremism has been relatively stable from the 1980s until around 2010. Usage of terms denoting far-left political extremism has been relatively stable since the 1980s, but usage started to grow in 2015.

The figure below highlights with vertical dashed lines three relevant years: 2008, when Barack Obama won for the first time the U.S. presidential election; 2014, the year prior to the 2015 entrance of Donald Trump into the U.S. political scene and 2019, the final year of our analysis. The usage of far-right-denoting terms grew substantially from 2008 to 2014 (243% and 359% in The New York Times and The Washington Post, respectively) and continued to increase from 2015 to 2019 (260% and 128%). These patterns indicate a strong polarizing dynamic arising before Trump, and continuing post-2015. In contrast, far-left-denoting terms did not grow in prevalence in either outlet between 2008 and 2014. However, between 2014 and 2019, the prevalence of such terms increased markedly (328% in The New York Times and 454% in The Washington Post).

Finally, we note that the growing prevalence of terms denoting political extremism in U.S. and U.K. news media is strongly associated with concomitant trends documented previously (here and here) about the rising use of terms denoting prejudice and social justice discourse in news media content; see Figure below.

Concluding thoughts

The biggest limitation of this work is that we cannot elucidate whether the media’s increasing use of terms denoting political extremism is driving, exaggerating or merely responding to concomitant rising political extremism in society. It is conceivable that far-right activity in society could have increased more markedly than far-left activity, justifying news media concern about it. It is, however, challenging to establish an Archimedean point of political neutrality to use as a reference for determining precisely what counts as political extremism.

While it is indisputable that groups which are labeled hard-right have been increasingly prominent in U.S. and European politics, it is also plausible that the center of gravity in established media newsrooms, as in other elite professions, has been shifting leftwards, especially as prestige news media is increasingly organized and edited by graduates from elite universities who tend to hold increasingly socially liberal beliefs. Therefore, a plausible explanation for the asymmetry in the prevalence of terms denoting left and right political extremism in news media content could be due to the ideological imbalance in newsrooms that might shape journalists’ choices of political adjectives.

Another potential explanatory factor for the rising incidence of political extremism-denoting terms in news media is the existence of financial incentives for media organizations to maximize the diffusion of news articles through social media channels by using language that triggers negative sentiment/emotions or using political out-group animosity to drive engagement in social media-based news consumption.

All of the aforementioned hypotheses (rising political extremism in society, the political biases of news media professionals shaping what gets labeled as political extremism and financial incentives motivating the usage of emotionally charged language) are plausible and consistent with our results on the rising prevalence of political extremism terminology in news media content. Yet, our methodology cannot adjudicate among them. This is, therefore, an open question for future research. Investigating the social ramifications of the increasing prevalence in news media content of adjectives suggestive of extreme political beliefs could be another relevant topic for future research.

To conclude, we find rising prevalence in U.S. and U.K. news content of terms that denote left and right political extremism. Most news media outlets tend to use terms that denote far-right political inclinations substantially more often than those pertaining to the far-left. The rising usage of terms denoting political extremism in news media started prior to 2015 and is analogous to concomitant growing usage of terms denoting prejudice and social justice discourse in news content (see here and here). The fact that U.K. media trends are similar to those in the U.S. suggests the existence of common factors driving these trends internationally.

Great study! Can you post the data from Figure 4? This would be useful for further analysis.

I did this same study for the Danish media in 2013. I only published it in Danish, but I found just about the same results you guys did wrt. relative mentions. I used data 2003-2013, and no time trend analysis.

http://emilkirkegaard.dk/da/wp-content/uploads/Omtale-af-ekstremisme-i-danske-medier-i-%C3%A5rene-2003-2013-en-kvantitativ-analyse.pdf

Hi David, thanks for this. Know anybody looking to hire for data analysis?